So, you’ve found your first client, congratulations! After all that hard work and grind, someone…

Aspect Ratio in Film From Past to Present

Welcome to another Film Editing Pro tutorial! In this post, our trainer, Leon, is going to dive deep into the topic of Aspect Ratios.

What are the different types of aspect ratios that you can use for a film? Why might you use one over another to tell a story? How have aspect ratios changed over time, and what’s coming in the future? Watch the video to find out or read the transcript below!

The Beginning

In 1888, Thomas Edison filed a document with the US Patent Office in which he conceived of a device that would do for the eye what the phonograph does for the ear. But before his team could build their first motion picture camera, they needed to establish the size of the film they would use.

In Edison’s employment was an engineer named William Dickson. Kodak was already manufacturing roll film for use in their popular box cameras. The film was 70 millimeters wide. Dickson takes the film, cuts in half, punches 64 perforations every foot, and 35 millimeter film is born. As the film is run through the camera vertically, the width of the frame is decided. The only decision that remains is the height of the frame. For reasons unknown, Dickson settles on the image being four perforations high. And so the first movie aspect ratio is created.

Working in 1.33

1.33 is less deliberate than you might think. Is almost arbitrary. Instead of working from the size of the frame outwards, they worked from the size of the film inwards. As is often the case, circumstance and technological limitations played a significant role in cinemas development, a pattern that we will see repeated.

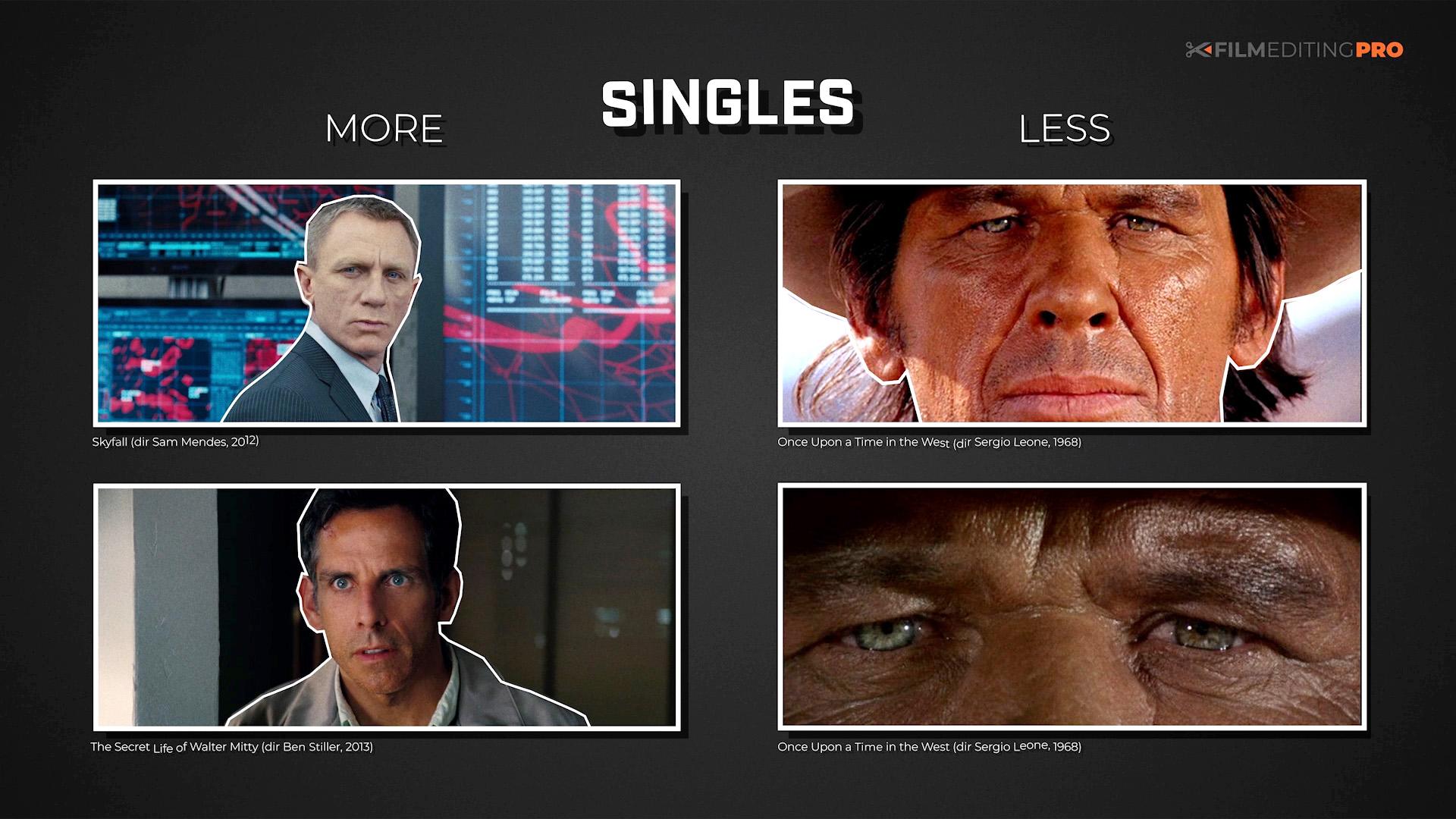

Let’s see how aspect ratio shaped cinema. We’re going to consider how composition and staging have changed, focusing on three types of shots, singles, groups, and environmental. 1.33 is great for shooting singles. The face can fill the frame, yet it doesn’t feel confined. It is difficult for the background to cause a distraction because we do not see much. Groups of two can produce a very intimate frame. Larger groups of people can present a challenge. Horizontal arrangements often called “clothes line staging” can make the frame look cramped. Depth or recessive staging works much better.

1.33 gives more room to compose vertically than wider aspect ratios. As 1.33 is more square, you can see why it excels with depth staging. Because at the frames lack of width, important compositional elements are often positioned vertically within the frame. This exposes a weakness. It’s not great for landscapes. In fact, the 1.33 frames seems most effective when it only has a single point of interest or focus. It doesn’t tend to handle two things very well. Look at the difficulty that the filmmaker encounters in this example below when trying to fit two points of interest into one frame. It’s not that it’s bad. It’s just not comfortable.

The Birth of Widescreen Cinema

For over 60 years, 1.33, or 1.375 which allowed room for an optical soundtrack, reigned supreme. In the 1950s with theater revenues dropping, Hollywood looked to widescreen to pull audiences back to the cinema. It’s a format they had experimented with, but never with any lasting success. Using larger film stock or cropping the standard academy ratio, all incurred different challenges.

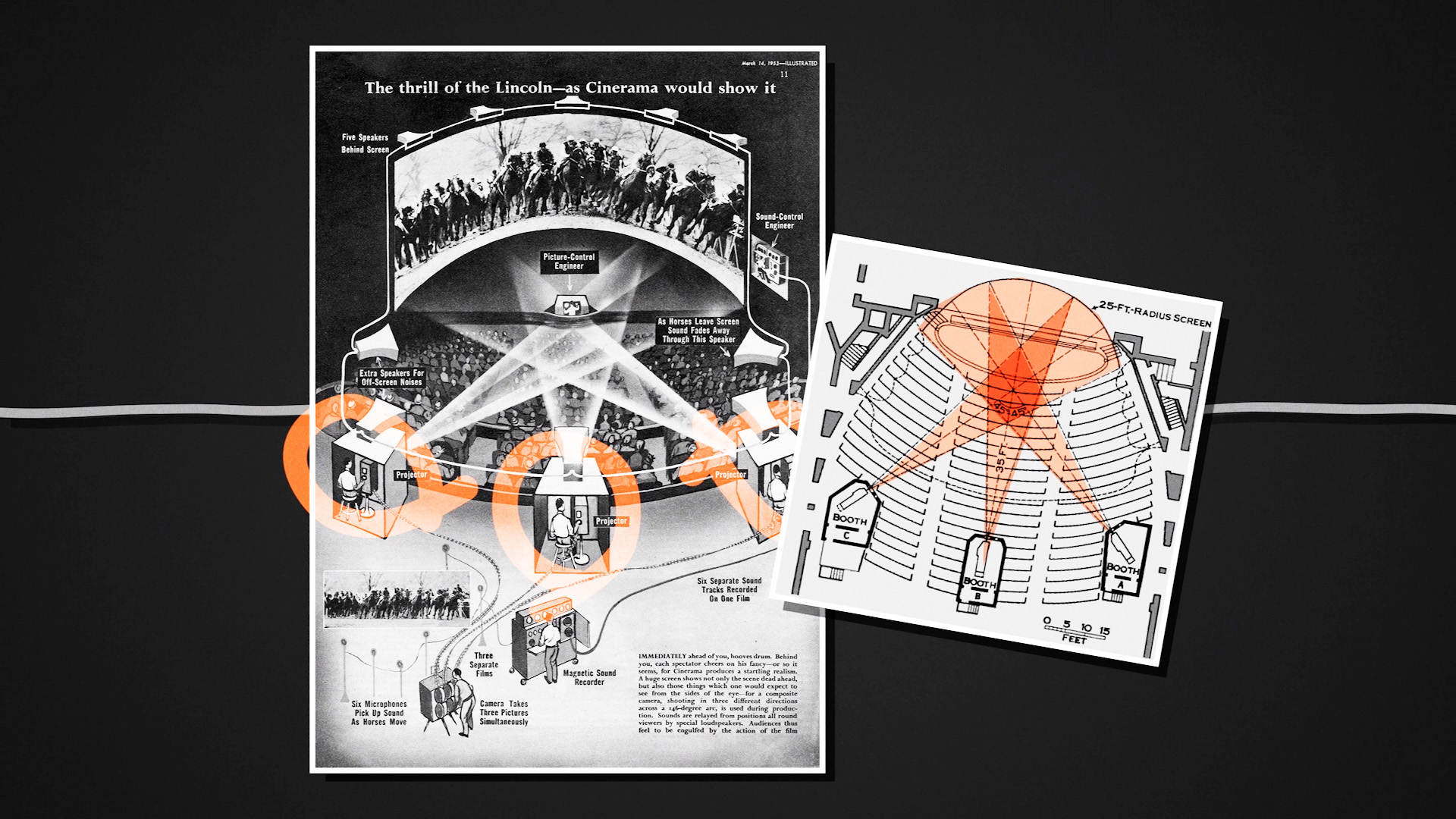

To solve this problem, in 1952, Cinerama was devised. On set, three 35 millimeter cameras was sandwiched together in an arc. In the cinema, three synchronized projectors seamlessly stitched the triptych back together on a huge 90 foot wide screen. Audiences loved it. Widescreen was here to stay. But before it could go mainstream, a better solution was required.

The Introduction of CinemaScope

20th Century Fox developed the answer, the system they called CinemaScope. They repurposed French technology invented to give tank drivers a wider field of view. By putting an animal thick elements in front of the cameras taking lens, they could squeeze a wider image onto a regular 1.33 frame. In the cinema, the projector would be equipped with another anamorphic lens that stretched the image back to the crutch shape. Cheap, effective, and accessible. CinemaScope lenses had a squeeze factor of two. When used with an open gate, it yielded an aspect ratio of 2.66. It was more commonly cropped to between 2.35 and 2.4 to allow room for an obstacle soundtrack.

How would this brand new frame affect the way films are made? Well, filmmakers had two options. They could treat scope as less a slice of the old frame blew up details in created abstract compositions, or they could treat scope as more a horizontal expansion of the standard academy ratio.

Let’s see how that works in practice. Now, a close-up is overwhelmed with all this surrounding space. This is important to know because a close up is not necessarily about how close you can get to someone, but it’s often about the exclusion of other information from the frame. So to achieve a close up, you have to block your actors carefully to get a clean single. Now the movie starts to inherit a different aesthetic because of the empty areas in the frame. Is that a good or a bad thing? It depends on the context.

Some filmmakers decide to go the other way, widescreen is less, pushing the closeup even closer, and in some cases, pushing it so close that it abstracts the image. The attention is back on your subject, but with a very different feeling. Techniques emerge to control the frame. Mise-en-scène or theatrical design is helpful. The set can be designed with the aspect ratio in mind. Elements of the set are used to control the frame. If, say, by putting an actor within a door or a window, we’ve essentially created a frame within a frame to get them back into a shape that better suits human dimensions. Over the shoulder is another popular tool used in scope to control the frame. The back of the actor’s head is used to reduce the size of the frame. This is often called dirtying the frame.

Other filmmakers decide to go for a compromise between less and more. The close-up chopped off at the next shot starts to become more prevalent in scope. It would never work in 1.33. It would be too intense. But with the extra width it works. How does the new frame handle two shots? In a medium close-up, a certain amount of intimacy comes from the audience’s inability to look anywhere else in the frame.

A similar framing in scope has a different aesthetic. It offers distraction and more space for the audience to roam. Of course, you can push closer to make the frame more intimate, but that too will have a different field. In the example below, to fill the frame, the filmmaker has chosen to rotate slightly off-axis. Keeping the shot partially in profile allows us to see the faces of both actors, but the shoulder and head of the nearest actor is starting to fill the frame. Mise-en-scène is also used to make the scene feel more intimate. The peripherals are darkened and made more claustrophobic.

How will scope handle groups of people? Small groups can sometimes be awkward, again, because of the empty space. So, clothes line staging becomes a very popular way of handling large groups of people. Depth staging becomes a little more difficult because of the lack of height. Mise-en-scène reduces the width of the frame a little while clothes line staging and a little depth is used to arrange the characters. In particular, this brand new super-wide frame excel at environmental shots. After all, widescreen mirrors the world around us because it’s panoramic.

Blocking in Widescreen

In the early days of cinema, everything was shut in Tableau style. The static camera would capture the entire scene without cuts. The audience was free to look around as the action unfolded. But technique evolved. The close-up and constructive editing was invented. The arts of filming a scene with singles and closeups became the norm. Filmmakers began to more tightly control where the audience looked.

Let’s talk briefly about blocking. CinemaScope called for an altered aesthetic. Because of the wider frame, the spectators eye is invited to roam making connections that in the standard 1.33 aspect ratio were more tightly determined. The shape of the frame means that two points of interest can be comfortably posed in the same frame. Whereas in 1.33, this sort of staging would look odd. This is almost a regression back to the Tableau style filming of old.

The move back to less restrictive framing might in part be due to how the size of the screen changed. As part of the conversion to CinemaScope, cinemas had to increase the size of their screens. A typical 1.33 screen was about 20 foot across. A CinemaScope screen was anything up to 60 feet. Scope offered many challenges, but this larger frame was where scope really started to become an advantage. Not only was the screen getting larger, but the frame felt bigger. A shot could essentially include two medium closeups. Thus, the frame was starting to affect more than just the image. It started to affect the way a movie was edited. When there is more information in a single frame, there is less need to cut. The size and shape of the frame aided cinematographers in composing images with greater context. The subjects, his muse and his environment can now fit into one single, allowing the audience to roam it freely, almost to participate in the process of discovery rather than be a passive passenger at the mercy of the editor.

The Evolution From CinemaScope to VistaVision’s 1.85

CinemaScope brought 1.33’s reign to an end. What came next? Is 1954, the year after the huge commercial success of CinemaScope. Paramount Studio wanted their own white screen technology because in part, they were sick of paying 20th Century Fox money to license their CinemaScope system, which wasn’t even that good. After all, it was a first-generation product. So, they took 35 mil film. And instead of running it through the camera vertically, they run it horizontally. Now, the width of the film no longer constraint the width of the image. They could make a wider image without making it smaller.

Paramount deliberately designed their new camera system to accommodate a variety of aspect ratios. The new landscape of cinema that featured different aspect ratios meant there was increasing disunity in the size and shape of screens featured in theaters. The practice of protecting for different aspect ratios became common. Natively, VistaVision shots in 1.5, but was intended to be exhibited in one of four aspect ratios, 1.33, 1.66, 1.85, and 2.0.

We’re going to focus on its most enduring legacy. Paramount’s recommended aspect ratio of 1.85. They had the ability to choose any aspect ratio. So why 1.85? VistaVision’s own promotional material says, “Optical experts believe that the frame that encompasses the comfortable viewing area is in the approximate ratio of 1.85 to one.” In other words, the aspect ratio of human vision is 1.85. This is a significant decision. At last, an aspect ratio that has actually been given some scientific thought.

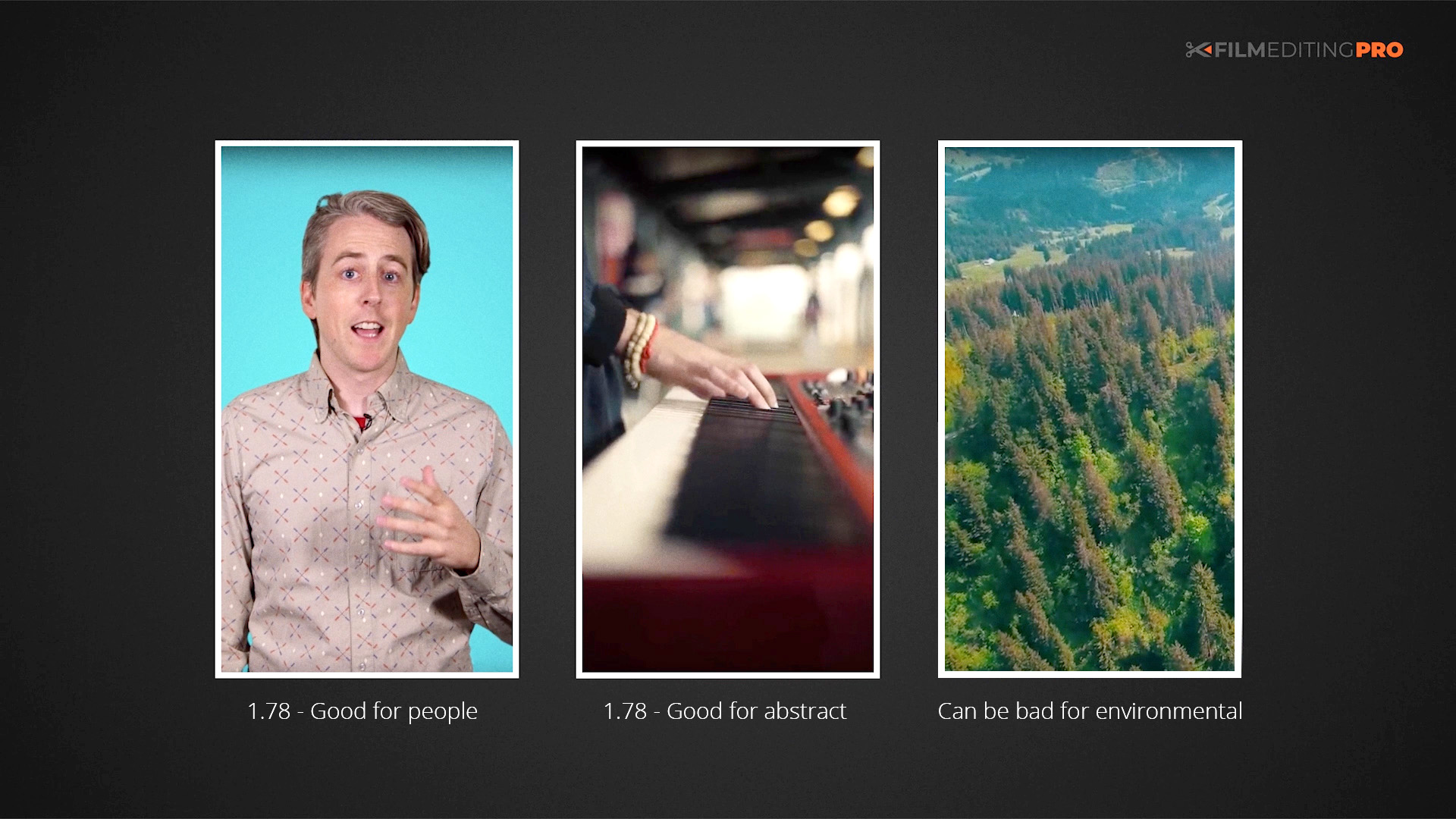

The first thing to note about 1.85 is that it’s a great size for people. It still offers a limited view of the environment, but not enough to require the filmmaker to work to tame a wider frame. It’s very versatile, but it doesn’t offer the abstraction of a 2.4 or 1.33. So you won’t see as many unusual compositions. 1.85 seems to just work. It’s very balanced, possibly a testament to its origins, the supposedly aspect ratio of the human eye. It can handle clothes line staging. And thanks to the frames extra height, it can also handle depth staging effectively. It can also do some of the same things that Scope can, like contain two shots in one. Environmental shots are no problem either. It can handle a variety of landscapes, both long and deep.

Take a look at how 1.85 can solve some of the compositional problems of 2.4 and 1.33. There is enough space to see the environment, but not so much as to be distracting. The greater height allows for more depth in the scene, allowing cinematographers to shoot if they wish 1.33-esque images. One more example, triangular composition that is awkward in scope is now comfortable in 1.85.

2.7, IMAX and More…

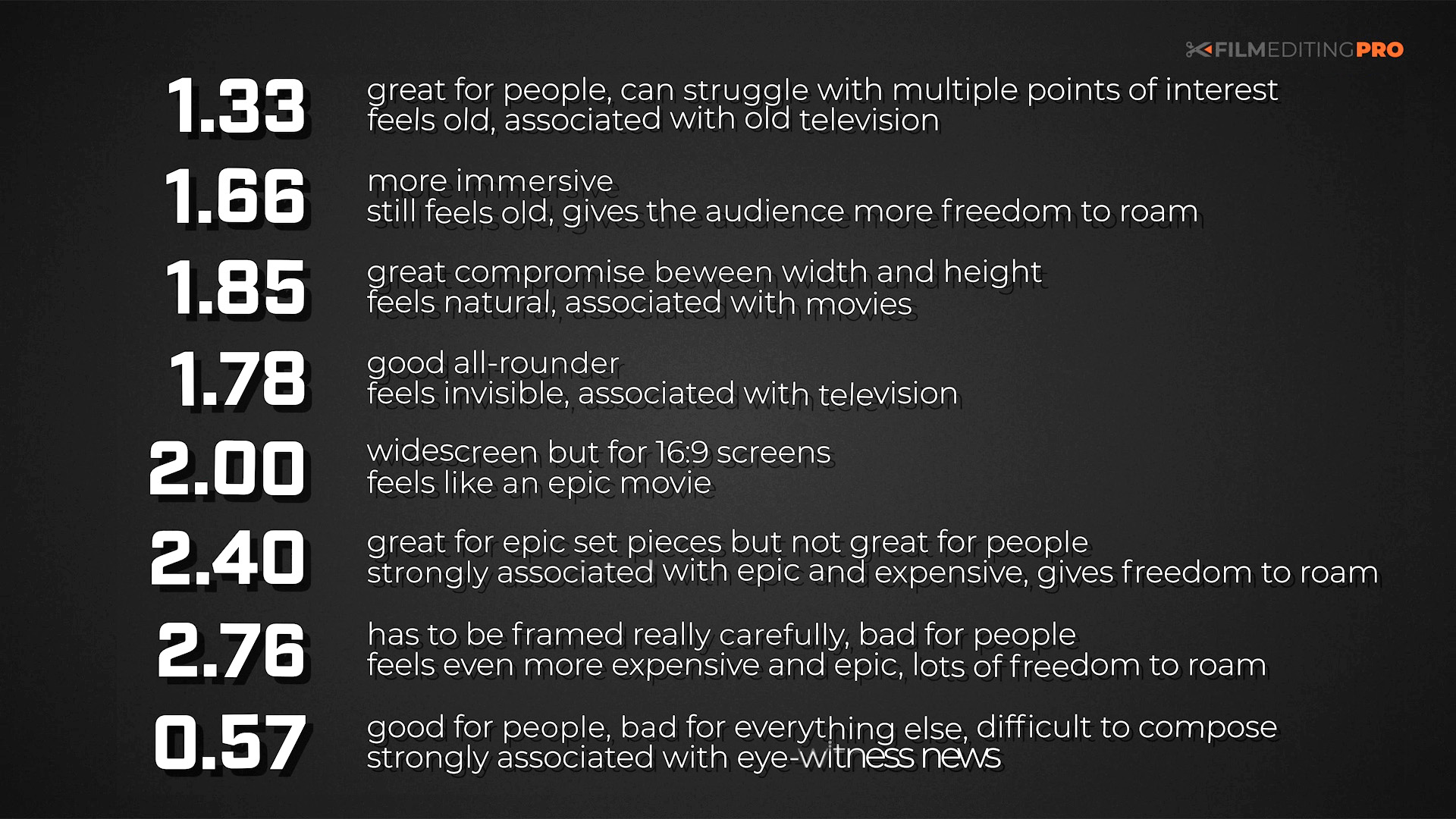

Many, many more aspect ratios have been shot and exhibited throughout the years. Some are based around new technology. Others are refinements of existing technology. Others yet are matted crops of existing formats. But you can think of 1.33, 1.85, and 2.4 as the small, medium and large of the world of aspect ratios. The merits of similar aspect ratios can often be evaluated by considering their closest equivalent.

Still, it’s worth considering a few more. Another attempt to address the resolution issues of 35 mil was the MGM 65 camera system. Later known as Ultra Panavision 70. Coupled with a 1.25 times anamorphic lens, MGM 65 yielded a stunning aspect ratio of 2.7. It’s capable of presenting incredible set pieces, but struggles with more intimate subjects matter. A lot of empty space is required to frame a clean single. In 2.76, clothes line staging is on steroids, but with careful and deliberate framing, it can create engaging compositions.

In the pursuit of an ever larger and more detailed image, IMAX was invented. Similar to the way that VistaVision turned 35 mil film on its side, IMAX bought the same revolution to 70 mil film. The IMAX frame is huge. IMAX is designed to be shown on a huge screen as wide as 100 feet. It makes it feel widescreen, but super tall at the same time. Similar to Scope, its large frame encourages the audience to explore, but now with a shape more similar to 1.33.

Aspect Ratios in the Modern Era

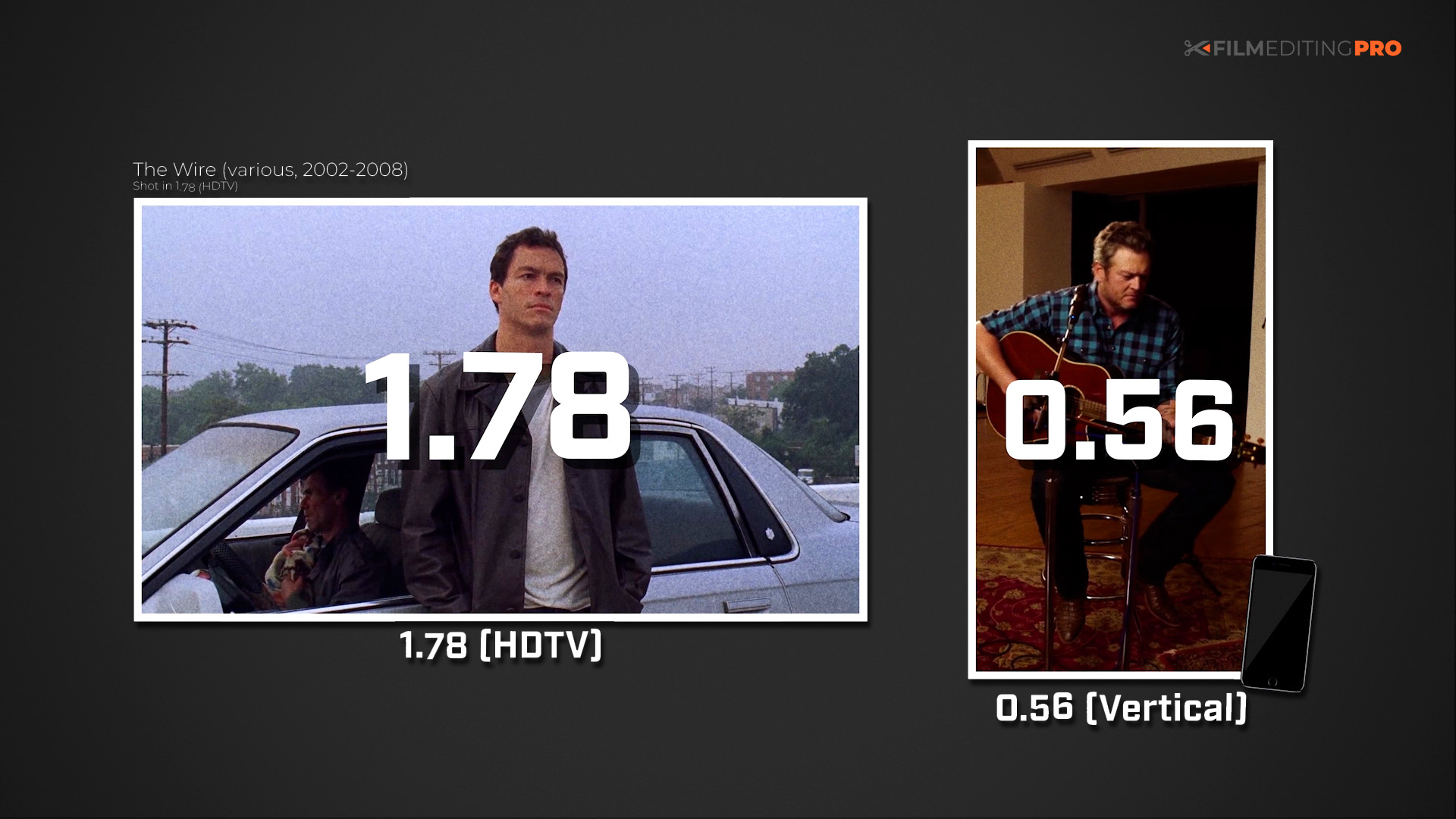

In the 1990s, technicians drew up the standards for high-definition television. They wanted to create an aspect ratio that worked equally well for legacy 1.33 TV broadcasts and movies shut in the popular 2.4 aspect ratio. So, they settled on the average between the two. 1.78 is so similar to 1.85. It shares all of the same strengths and weaknesses.

In a funny kind of way, technological innovation has driven the rise of the vertical aspect ratio. Smartphones shoot and display 1.78 or close to. But to do that, you have to rotate them 90 degrees. A mixture of human nature and poor ergonomics means a lot of people don’t rotate their phone. It’s great for people because people are tall and thin. It works well for some abstract compositions, but it really struggles with anything environmental.

2.0 is currently enjoying a renascence. It’s existed in various guises for years, but has recently become a go-to format for streaming services like Netflix, Amazon and Apple. It’s a nice middle ground between 1.78 and 2.4. People love widescreen. However, excessive letterboxing on small screens can waste precious screen space. So, 2.0 seems to offer a good compromise, the allure of wide screen without the waste of letterboxing.

It’s worth briefly considering what’s happened to the size of our screens. Most people tend to watch TV on a screen no smaller than 32 inches, but typically around 40 to 50 inches. But something interesting has happened since the invention of the smartphone. It used to be that the size of the device people watched content on was getting steadily bigger. Smartphones have turned that trend around. Does the size of these screens affect the way we would choose to use a particular aspect ratio? For example, is it harder for audiences to roam a 2.4 aspect ratio looking for subtle clues placed by the cinematographer when the screen measures may inches across?

Which Aspect Ratio is Best?

Different aspect ratios suit different composition of styles and different subject matter. It’s undeniable that a face better suits the dimensions of taller aspect ratios and that panoramic vistas suit wider formats. But beyond that pragmatic differences, different frames elicit different psychological and emotional responses. At the risk of generalizing, 1.33 will forever remind many people of old movies and standard definition television. It can instantly make something feel old.

Scope is often associated with high budget action movies. For many, it instantly feels expensive and epic. More moderate aspect ratios like 1.85 have a more neutral perception. And on a standard high definition TV, nothing is more invisible than its native aspects ratio. 1.78. Others are driven by perhaps the most pragmatic motivation, the aspect ratio of the device the movie will be seen on.

For years, movie producers have been influenced by the size of the screens in cinemas. Television producers have faithfully transitioned from 1.33 to 1.78 as they follow the consumer trend. And now, online producers are protecting for, or sometimes straight up shooting in vertical. Some movies even feature multiple aspect ratios such as the example below from Interstellar. Changing aspect ratio can be used to differentiate time periods, or maybe underscore the epicness of a battle scene.

In Jurassic World, John Schwartzman, the DP, wanted to shoot in 2.4, but the producer, Steven Spielberg, wanted the film shot in 1.85 like the original because it allowed more headroom for the large dinosaurs. In the end, a compromise was reached in the form of 2.0. The film Ida was shot in 1.375 because it is evocative of the era in which the film was based. The story is set in a convent and symbolizes its nuns and novices thoughts of God and heaven above by using this tool aspect ratio and often framing with lots of headroom.

In The Grand Budapest Hotel, Wes Anderson wanted to differentiate between the three time periods featured in the story. Therefore, the film features three aspect ratios, 1.375, 2.35, and 1.85. Damien Chazelle wanted La La Land to elicit the feel of old musicals shot on CinemaScope. So, they shot it in scope with an aspect ratio of 2.55. Joss Whedon and Seamus McGarvey decided to shoot The Avengers in 1.85. According to some interviews, that decision was heavily influenced by just one shot in the movie, the eponymous shot where the Avengers assembled. Tall, large and small can all fit more easily into a 1.85 frame than they would have into a 2.4 frame.

There are many different reasons to shoot in a particular aspect ratio. But whatever your reason, make sure you aren’t just slapping black bars on your footage because it looks cool. Let the story drive your decision-making process. And once you’ve chosen an aspect ratio, design every set, every composition, and every cut to suit that frame.

Wrap Up

Good videos are all about story. The frame is the window through which we experienced the story. The frame has taken on many shapes and sizes. Regardless, it is simple, four sides, rectangular in shape. But just as complex does not mean complicated, simple does not mean simplistic. The frame is a motive. It has nuance and history. But at the end of the day, we don’t want people to be looking at the frame. We want them to be looking through the frame. If you can create something invisible, then you have achieved your goal. All of the attention, all of it should be on the story. Aspect ratio is a tool, one of many that we have in our arsenal. Use it well, use it with understanding, and use it for a reason.

Leave Your Thoughts & Comments Below: