So, you’ve found your first client, congratulations! After all that hard work and grind, someone…

Tips on Presenting Rough Edits & Getting USEFUL Feedback

Assembling that first edit brings a flood of emotion and excitement. After months of planning and weeks of shooting, the edit is a significant milestone. Finally, the filmmaker’s vision is translated from the abstract confines of their mind into a tangible product that can be shared, experienced and evaluated.

But how do you know if you’re on the right track? The script can only provide so much guidance. It’s your job to choose the best performances, shots, etc. and stitch them all together seamlessly to tell a powerful story. This is where you need to start seeking feedback.

In this tutorial we’re going to explore the following topics:

- Why is early feedback important?

- When should you show a rough cut?

- Who are the best people to ask for feedback?

- Five practical tips for presenting early edits

- How to interpret and address the notes

Why is Early Feedback Important?

It’s natural to want to start sharing your work as soon as possible and to seek feedback. This has two benefits:

Critique – Movies are created for people to watch. If people don’t enjoy or understand it, then it’s not fit for this purpose. Constructive criticism will help you to produce a better edit.

Confirmation – Editing is hard work! We don’t typically enjoy sifting through bins looking for clips. We endure because we love the end product. That glimpse that the audience is going to love the finished product can be a powerful motivator.

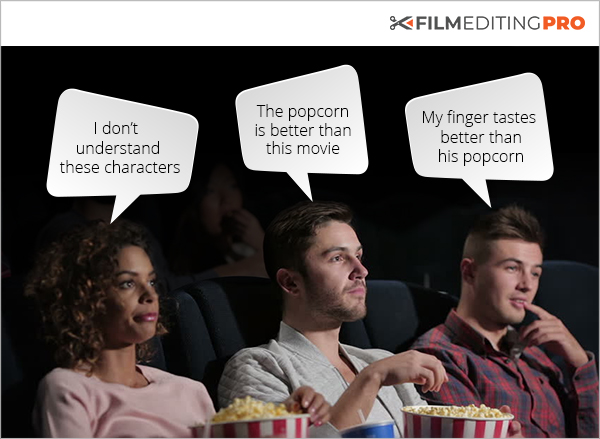

So, you invite someone to watch your early edit…

It’s easy to get frustrated or bummed out by such feedback and misunderstandings. You might even worry that they think you are a bad editor. A common reaction is to want to hide your work, not share it until it’s well polished and tightened. But this approach can limit an editor’s ability to work effectively.

When Should You Show A Rough Cut?

You see, once an edit is finished (or close to), we’re less inclined to make changes because of the effort involved and our emotional attachment to our ‘baby’. And if major changes are needed, we’ve wasted time polishing an edit that is destined for the cutting room floor.

At the other end of the spectrum is an edit that is so underdeveloped, it’s hard to evaluate its problems. Showing work that is too rough is just a waste of people’s time.

Tip: If you have to explain your edit before someone watches it, then you might need to work on it a little more before presenting! Let your edit do the talking.

Somewhere in the middle is the perfect balance. When your edit is just rough enough, or ‘ugly’, it’s sufficiently assembled to communicate your vision but it’s still in a transformable state. To help people to concentrate on critiquing the edit, make sure that gaffes in the image or sound do not distract the viewer.

- Audio – Always make sure your audio levels are set appropriately, smooth out room tone and fix any obvious issues. Where appropriate add rough foley and sound effects.

- Image – Always apply some basic color correction to ensure everything is well exposed.

- Edit – Some scene transitions can be quite abrupt. J-Cuts, L-Cuts and the score help to make these transitions more intuitive. It’s always worth spending time roughing in these elements.

When you have pushed your edit as far as is reasonable, your ‘ugly’ edit is ready to be shown!

Who Are the Best People to Ask for Feedback?

At a time when your own emotions might be clouding your judgement, you need constructive criticism that is objective and logical. Advice is often only as good as the person giving it! Who can you ask for worthwhile feedback on your edit?

Consider your options…

Other Editors: If confidentiality allows, are there colleagues you can share your work with? They understand the workflow and have proper expectations of an early cut. Perspective trumps ability when it comes to providing critique. It doesn’t take a better editor to see your mistakes, it often just takes a different editor.

An Outsider: Consider showing someone who has nothing to do with the project. Someone involved in the production might be overly focused on looking out for their favorite shot, or how their performance is shown. Often, the less emotionally involved they are with the project, the more objective they can be. Sometimes, a non-filmmaker’s perspective is the most helpful!

A Friend: Hang on! This might seem counter-intuitive. Constructive criticism is all about where you can improve rather than someone massaging your ego and telling you how great you are. Yes, you are 100% right. Your edit needs to be torn to shreds by someone to help make it better but it’s so much easier to take such criticism when it comes from a friend. You know you have their respect and that the ensuing conversation is not about you, but about the edit. A good friend will give honest advice.

Tip: Don’t become resentful when people tell you things you already know. Foster an environment where people feel free to express themselves regardless of whether it is a point you might have already considered.

5 Practical Tips for Presenting Early Edits

Here are 5 things to keep in mind when presenting early edits:

1. Show Alternate Cuts – Sometimes it becomes apparent that the elements of the script or the director’s plan don’t work as well as hoped. In that instance it might be worth preparing two edits. Try presenting the ‘bad’ edit first, letting them see the problem for themselves if the cut follows the script exactly. Then kindly present your alternate version as a suggestion. Remember that the entire project is their ‘baby’ too, not just the editors. Help them to understand the challenges you’ve encountered and be kind throughout. This might seem like more work but you’ll make a friend in the process, helping people invest in your edit rather than resent it.

2. Have Good Communication – When gathering feedback, ask specific questions but don’t ask leading questions that pressure people to give you the answers you want rather than the answers you need. You wouldn’t want to ask a question like “So on a scale of 1-10, do you think this was a 9 or 10?” Rather, ask open questions like: “Was there anything you found distracting?”, “What did you think the message was?”, “How do you think the character feels?”

3. Use Placeholders – If an element will be provided later in post-production – for example a finished sound effect, visual effect or pickup – use a placeholder. It can be a reference image, a storyboard, a proxy sound effect, stock footage, etc. It could even be an onscreen caption. Whatever it is, just include something that lets your audience know where the edit is unfinished.

4. Show Appreciation – Always show appreciation, even when you think the critique is incorrect. You don’t want to discourage someone from giving further feedback, because their next piece of advice might be golden!

5. Ask more questions – Remember, discuss, don’t dismiss. It’s often helpful to follow up on comments with a clarifying question. The better you understand their viewpoint, the better you can diagnose your edit. When phrasing questions consider who you are talking to. You may need to help non-editors to articulate their thoughts.

How to Interpret and Address Notes

It’s a great idea to make notes when showing your early edits. It helps you to remember everything, but it is also a visible display of respect for the person providing comments. Now that you’ve gathered feedback it’s time to work on your edit. Here’s some tips:

- Allow Time. It’s natural to form an emotional attachment to your early edit. After receiving feedback, it might take time for your mind to clear so that you can see your work more objectively. Today you might not see it, but tomorrow you might agree.

- Sort. It’s important that you learn to differentiate between good and bad feedback. Some comments are misunderstandings as a result of the rough edit.

- Think. Sometimes feedback comes in the form of a suggested solution. Even if their solution isn’t the best idea, their instincts might have identified a problem that they can’t articulate (i.e. pacing issues, poor shot selection, etc). Finding out what made them feel the way they did will help you to identify the real problem.

- Act. Address each issue, especially if it’s from your client. Sometimes they may insist on changes that you disagree with, but with a little work you can apply their feedback in a way that makes them feel included but yet preserves the integrity of your edit.

Wrap Up

Presenting a rough cut can be a bit stressful and sometimes a blow to the ego. Just remember to keep an open mind, realizing that a production is team effort and that everyone wants the same thing – a great finished piece.

When choosing the right stage to show your cut, remember that a measure of polish is needed before presenting your edit but keeping it a little ugly puts you in a better position to act on comments. The timeline will physically have less complexity to it, making it easier to manipulate and you’ll be less married to the work you’ve already done.

And finally, when assessing feedback, you must defend your own vision for the edit, but well-considered constructive criticism from the right people can only improve the cut. And, the earlier you can gather feedback, the easier and more effectively changes can be made.

If you’d like to learn more about film and drama editing, be sure to sign-up for our course, The Art of Drama Editing. Enrollment closes on August 10th at 11:59pm Pacific Time.

Leave Your Thoughts & Comments Below: