So, you’ve found your first client, congratulations! After all that hard work and grind, someone…

Editing vs Real Life – What Drives the Cut? Part 1

The cut. Simple, ubiquitous, invisible. What is it, why does it work, and how can you use it correctly? Watch below or read on!

A cut is the instantaneous transition from one camera angle to another. It’s hard to imagine cinema without the cut. It controls the flow of information, directs the audience’s attention and sets the pace. Yet once upon a time, movies only featured one shot. Jump in. Buckle up. And hang on! In this 4-part series, we’re going to examine the topic of ‘What drives the cut?’.

The Origin of the Cut

First, we need to talk history. In the earliest days of cinema, movies were short vignettes of variety acts. A train, a dancer, a magic trick. But grander things were to come.

As cinema transitioned from a novelty to a serious storytelling medium, it simply mirrored theatre. Most films were shot in tableau style – French for ‘living picture’. You set up a scene, turn the camera on, the action plays out, the scene ends and you turn off the camera. Cutting of the film was used simply used to trim stock to length or to assemble related scenes in a linear sequence. There wasn’t really any cutting within the scene. For example. in 1898 Robert W Paul made Come Along, Do! An elderly couple is having lunch outside of an Art Exhibition and they decide to follow some people inside. The camera cuts to a shot that shows what they do inside

Cutting between different locations was an important milestone but not revolutionary. Cinema’s closest facsimile, theatre, had long made use of multiple sets in a single story. So, it was a natural evolution in film for new camera angles or locations to be required as the story played out. However, these kinds of cuts were more pragmatic than creative. The cut was still capable of more – a lot more.

Cutting Creatively

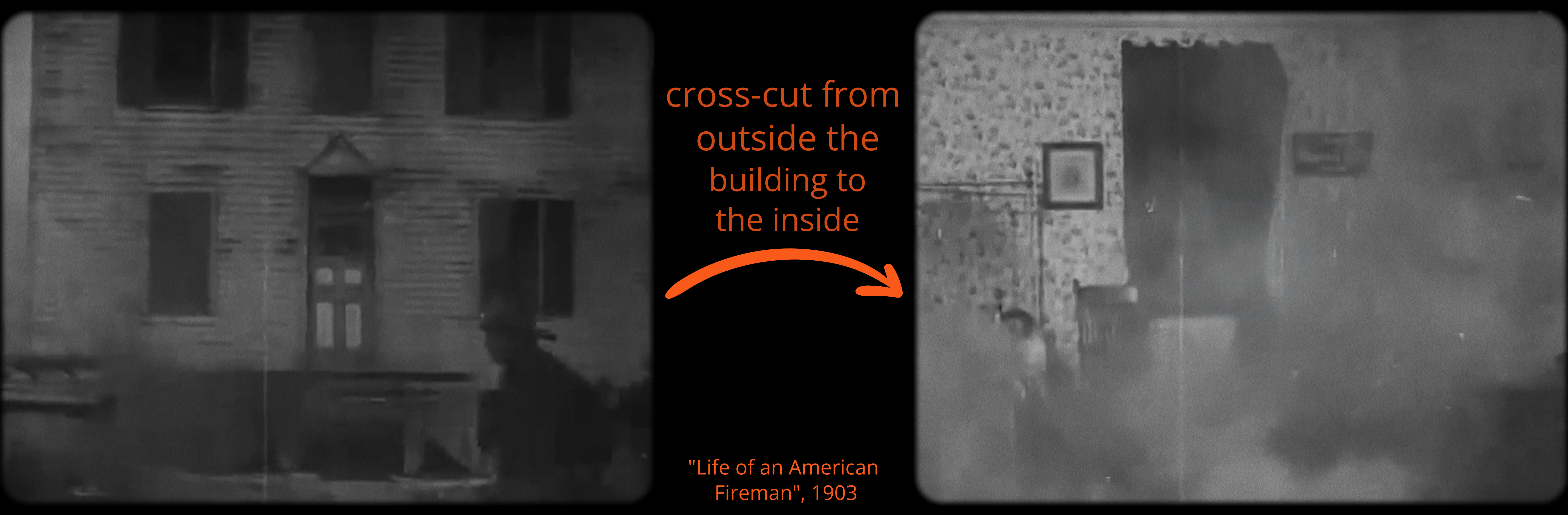

Filmmakers across the globe began to experiment. 1903 saw the releases of Life of an American Fireman and The Great Train Robbery. Both featured cross-cutting, a then-uncommon technique of cutting between events occurring simultaneously in different locations creating a composite film, one where the narrative was made of two or more different yet intertwined threads. But a lack of variety in the framing and sizing of shots hindered the edit’s creative potential. Even revolutionary films like Battleship Potemkin featured mostly medium or wide shots and the art of filming a scene with ‘coverage’ was not yet common place.

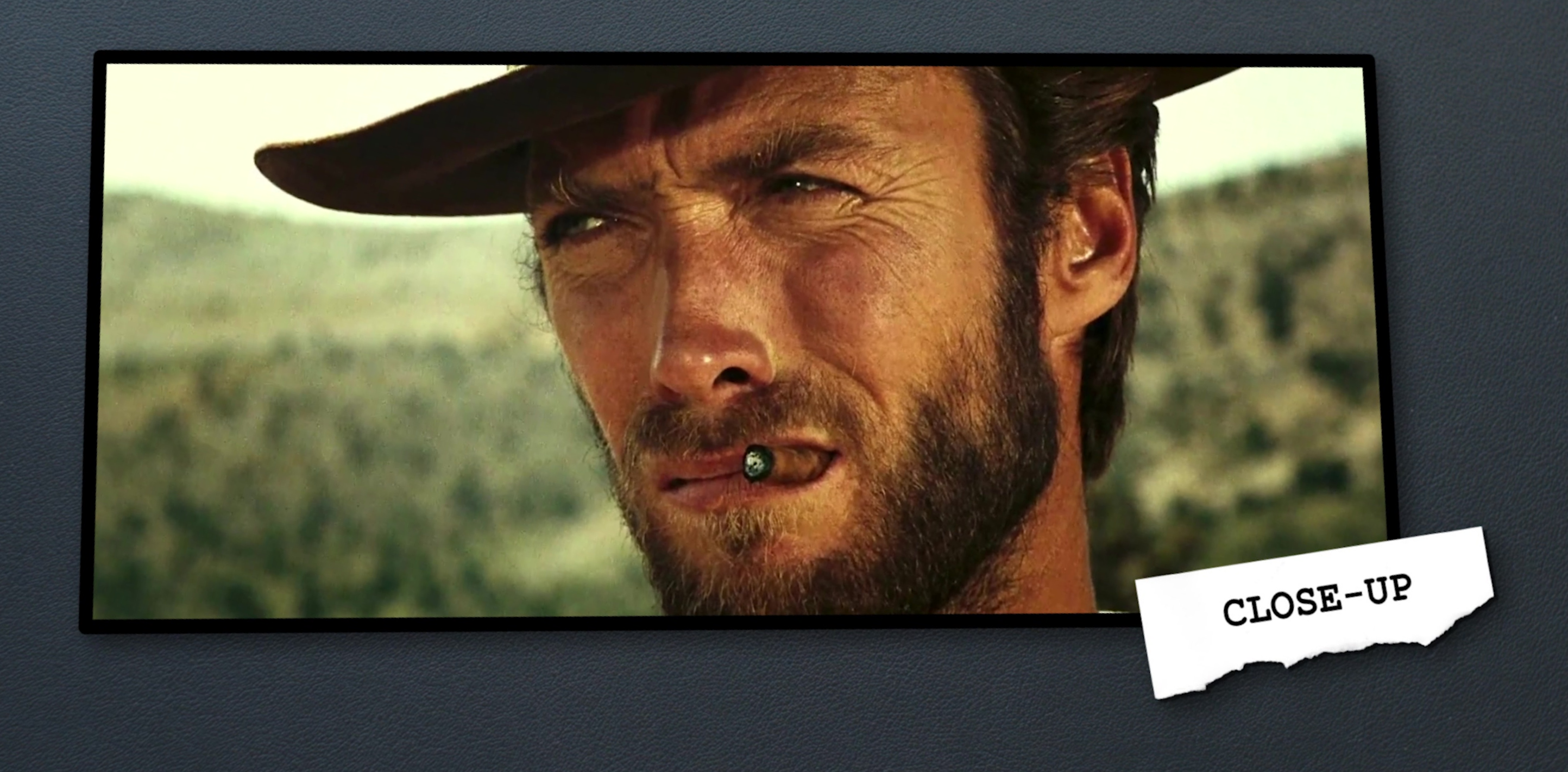

In 1928 Carl Theodor Dreyer made dramatic use of closeups in The Passion of Joan of Arc. While he certainly didn’t invent the closeup, no previous filmmaker had used them so extensively (almost exclusively) within a scene. By showing just one thing in the frame, a closeup excludes everything else in the scene. There is little need to cut between different wide shots as they will both contain similar information – everything. But a closeup is different.

This new style of cinematography allowed for a revolutionary edit. One where the editor could cut within the scene, not just in between scenes or when a change of angle was needed to follow the action. It’s easy to overlook how unlikely these developments in cinema were. Cutting is counter-intuitive, especially within a scene. It doesn’t mirror our real-life-experience.

Think about that for a minute.

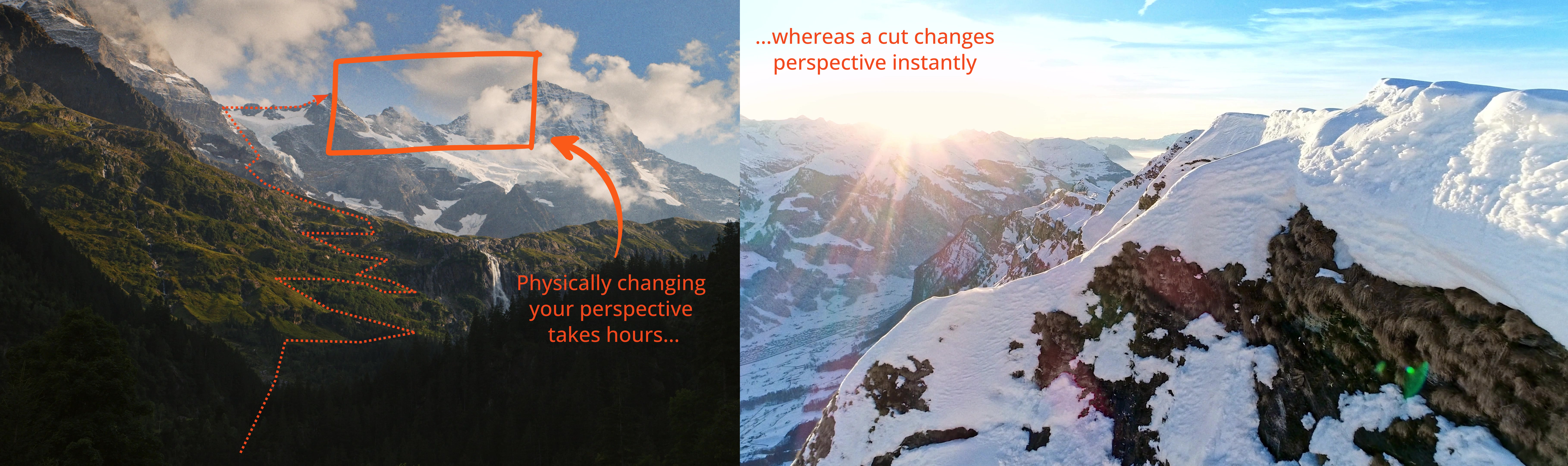

Our perspective is constant and unchanged. If you were to attend a play in a theatre, unless you REALLY want to annoy the other patrons by wandering around, your view of the stage does not change. Or say if you hiked to a panoramic viewpoint, but decided you wanted a closer perspective, it could take you hours, or even days to achieve that. Yet an edit allows the filmmaker to change your perspective and even travel through time in the blink of an eye. It’s no wonder these techniques took so long to develop

The cut had transitioned from being a pragmatic tool – one used to assemble scenes shot on different reels, follow the action or to hide the process of filmmaking – to being a creative tool, one that could be called upon to add drama and interest to a story.

Cutting Becomes an Art Form

By the 1930’s the editor had a comprehensive toolbox. They had an understanding of best practice thanks to concepts like the 180-degree rule. They had an understanding of the power of editing, thanks to the work of filmmakers like Lev Kuleshov who demonstrated how careful selection of the shots in an edit can imbue meaning, with his infamous tests of the expressionless model. And finally, variety of compositions and angles, thanks to directors like Carl Theodor Dreyer who popularized closeups with his sensational coverage in the Passion of Joan of Arc.

The art of editing exploded and by 1934 the Best Film Editing category was added to the 7th annual Academy Awards. Film Editing was becoming recognized as an artform unto itself, not just a tool for filmmakers to stitch together their footage. Cutting technology remained relatively unchanged for almost a century until in the 1980’s digital non-linear editing was invented. No longer inhibited by having to physically cut and splice film together, editors could more easily experiment – spurring further growth and creativity.

Wrap Up

As obvious and natural as the cut feels to us now, its invention was not obvious or intuitive. Will the cut make cinema better or worse? Just because you can cut, should you? How can editing contribute to the development of the story?

To answer these questions, you’ll have to wait until part 2 of this series. In the next post, we’ll be exploring the concept of micro and macro editing and how we can use both to tell a compelling story with film.

As always, for more tutorials about creative editing be sure to visit our training page. There, you can sign up for hours of free sample videos and more information about our full courses.

Leave Your Thoughts & Comments Below: