So, you’ve found your first client, congratulations! After all that hard work and grind, someone…

Questions & Answers – What Drives the Cut? Part 4

Editors are presented with many choices. Which shot? How long? In what order? These choices have a huge impact on the audience’s enjoyment of a scene. What considerations should inform these choices? Find out in the final piece of our 4-part series, ‘What Drives the Cut?’.

In Part 1, we examined the evolution of the film editing as an artform. In Part 2, we dissected what makes a story captivating. In Part 3, we compared cutting for story vs spectacle. Now let’s put this all together.

Understanding the Footage

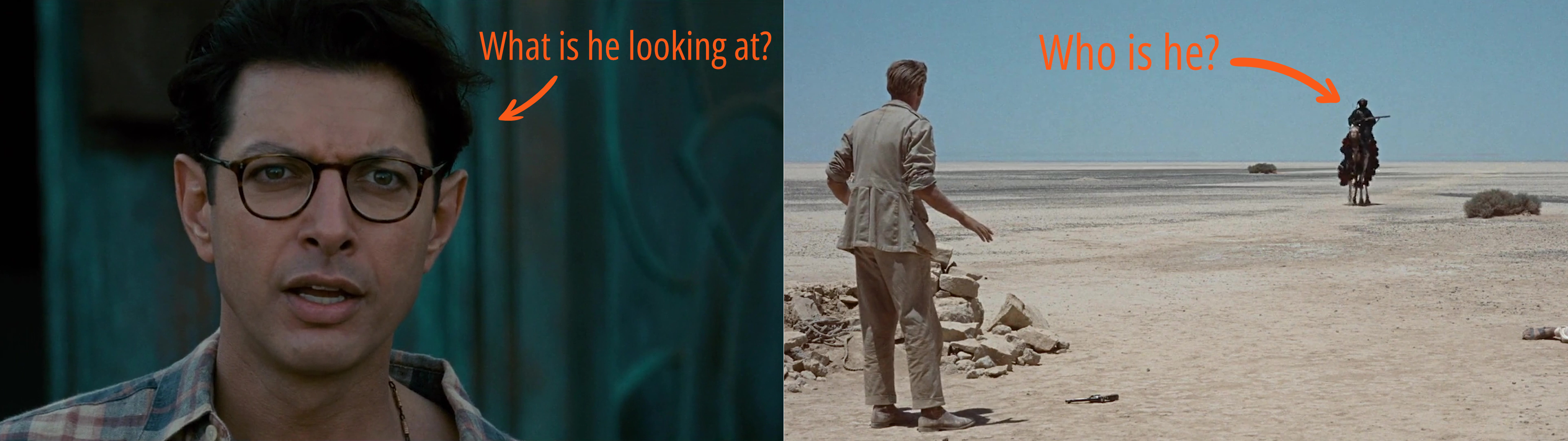

To edit well, you need to understand your footage. Each shot in your final edit should serve a distinct and unique purpose. A shot is capable of making the audience ask a question, and is also capable of answering a question. In fact, it can do one, the other or both. Questions usually arise when information is excluded from a frame. For example, the shots below pose questions to the audience such as ‘What is he looking at?’ or ‘Who is he?’.

Answers are provided by information in the frame. Different types of shots excel at conveying different types of information:

- Extreme close-ups help us to understand a person’s feelings

- Close-ups are great at teaching us about people, who they are

- Medium shots are useful for showing what people are doing

- Wide shots are great for showing information about locations

Ask and Answer

So, which information will you give the audience first? Will we show them who is in the scene? Or where the scene is happening? Or maybe what they are doing? In a well-constructed scene, the audience is going to pine for the information we’ve not given them.

Questions and answers should be spread throughout your edit because questions keep your audience watching, but answers are what make them enjoy your movie. Avoid shots that convey similar or identical information.

Imagine reading a novel that says: ‘He opened the door and went through. Through the door he went after he had opened it.’ That’s just boring! Try writing your edit out in words, one sentence per cut. If it’s boring, then your edit is probably boring.

Just like a good murder mystery – structure the flow of information to progress from less to more. On a large screen, wide shots show a great deal of information. Maybe consider starting with close-ups and moving to mediums and then wides as the scene progresses.

Ask yourself questions like: What information should I give my audience first? Should I show them where we are, who is here, or what they are doing first? As questions are answered, you’ll want to pose further questions to your audience otherwise they will lose interest.

As a general rule of thumb, the beginning of a scene will pose more questions and the end of the scene will provide more answers. And of course, you’ll finish your scene with some lingering questions in order to prime the next scene. These are known as open loops.

What about Single Shot Films?

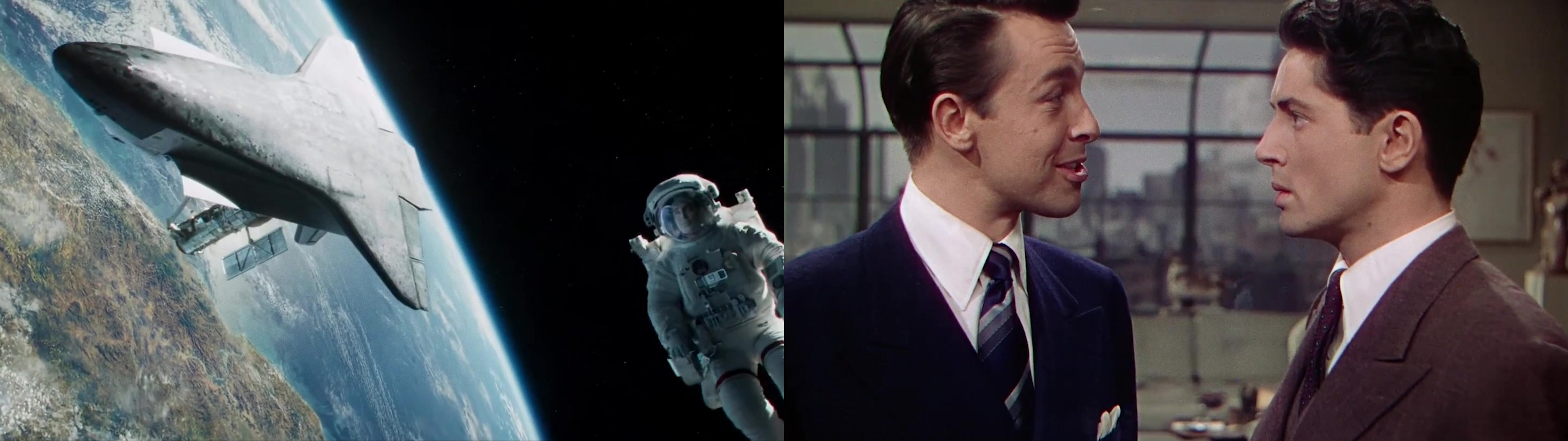

If cutting is so important though, how come some films don’t feature any at all? Alfred Hitchcock was the first to tangle with the idea of an entire film playing out in a single shot. The rise of digital filmmaking has made this prospect even more accessible. There are many examples of single-shot films and films that feature extremely long takes – Films like Gravity, a Touch of Evil, and the Panic Room. It’s even become a signature for some directors like Stephen Spielberg. The ‘Spielberg oner’ is a well-studied subject.

In a well-constructed long-take, instead of cutting, the camera dynamically moves from composition to composition. Even without cuts, the sequence still embodies the principles of cutting, controlling the flow of information. Posing questions by selectively withholding information from the frame and revealing that information by camera movement or careful blocking. Consider this example from Gone with the Wind…

Scarlett looks shocked. The camera pulls out to reveal the scale of the injured soldiers. Instead of cutting to a wide, the camera craned to a wide. The shot went from less information to more information.

Or consider this example from Jurassic Park. The camera starts wide, showing Dodgson arriving in a taxi but without revealing anything more about the location. The camera moves into a close-up of his bag and then to a medium showing him clearly looking for someone, compelling the audience to wonder what’s in the bag, and who he’s looking for.

The edit cuts to a shot of Dennis, answering one question yet posing another – Who is he? The continual camera movement promises that an answer is imminent, fueling the audience’s anticipation. Even without cuts a good long-take still embodies the principles of a cut.

Wrap Up

So, what can we say in conclusion?

The humble cut is more creative than any glitch or wipe transition could be. The editor can use the cut to shape the flow of information in a scene, connecting shots together in a chain of cause and effect, posing questions and delivering answers that compel the viewer to keep watching. It’s those questions and answers, that are the driving force behind a cut.

Pragmatic in the early days of film, the cut has evolved into a powerful creative tool. Cut with purpose. Don’t be redundant. And, keep your viewer guessing, always leaving a bit unsaid…a mystery waiting to be solved.

Hopefully you enjoyed this 4-part series! For many more editing tutorials, be sure to check out our training page and sign up to receive hours of free videos.

Leave Your Thoughts & Comments Below: